I want to tell you the stories of two men, almost exact contemporaries and both committed ministers of the Gospel.

The first is William Ashley Sunday, born in 1862 in Iowa. William’s father was a Union soldier killed in the Civil War, and William himself bounced around during his childhood, spending some time in an orphanage. He was blessed with athletic skill, and as a twenty-one year old phenom he signed to play professional baseball for the team that was then called the Chicago Whitestockings. By then they called him Billy, and in Chicago Billy Sunday was exposed for the first time to the sin that is endemic in the world, including the effects of alcohol abuse on working people. These revelations and a chance encounter with a preacher on a Chicago street corner led Billy to a conversion experience. All the other things in his life subsided, and Jesus became his lord and king. Billy gave up baseball and began holding his own revival meetings. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Billy was receiving invitations to preach in large American cities. Eschewing churches or auditoriums, Billy’s advance team built huge wooden arenas called “tabernacles” in cities where Billy appeared, adding to the anticipation of his revivals. Decades before Billy Graham appeared on the scene, Billy Sunday was a prototypical mass preacher. He stomped and yelled, employing exaggerated gestures and colloquial language. He moved millions. And he believed that the key to saving the world was for people to invite Jesus into their hearts to be their king. For Billy, this was an entirely internal affair. Jesus’ kingdom was interior, the realm of the heart.

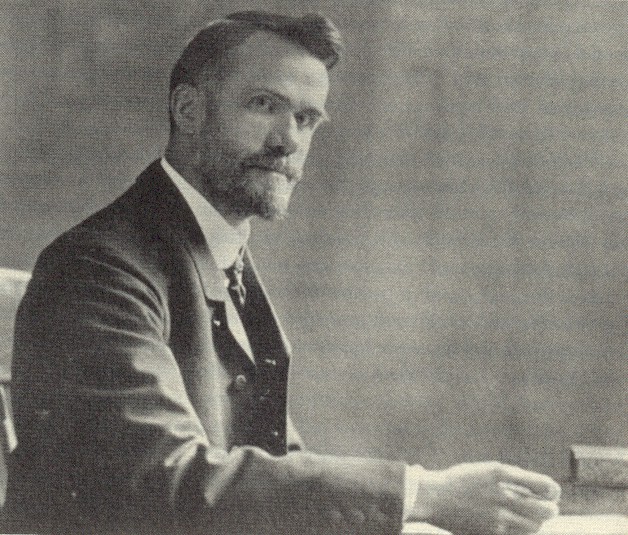

In 1861, the year before Billy Sunday was born, a baby boy named Walter Rauschenbusch was born in Rochester, New York. Walter was the son of a Baptist seminary professor, and it soon became obvious that Walter would follow in his father’s footsteps. He grew up and was ordained, and in 1886—the same year Billy Sunday met the street corner evangelist in Chicago—Walter Rauschenbusch took a call to serve as pastor of Second Baptist Church in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen. Walter’s experience in New York was as transformative as Billy’s in Chicago. In the Hell’s Kitchen of the late 1800s, he witnessed immigrant communities in sordid living conditions, labor exploitation by industrial giants, and government indifference to the plight of its most vulnerable citizens.

Walter Rauschenbusch read his bible again, and he realized that in the Gospels Jesus spends most of his time talking about the kingdom of God. Jesus’ actions, Walter also recognized, actually transformed the real, physical lives of the people he met: Jesus set captives free; he offered healthcare to the sick; he overturned the moneychangers’ tables and convinced swindlers like Zacchaeus to deal fairly with people. Jesus is a king who came to change the world, not only our hearts, and the Gospel, Walter decided, is a social Gospel. With an evangelical zeal as strong as that of Billy Sunday he wrote and preached on the Social Gospel, giving the new Progressive Movement of the early 1900s a powerful Christian voice.

I daresay these two names were unknown to most of us: Billy Sunday and Walter Rauschenbusch. But in the first two decades of the twentieth century, they were national celebrities. There were no bigger names. One filled cavernous rooms. The other sold best-selling social commentaries. Both were absolutely committed to the idea that Christ is king, but their visions for what that looks like were as different as night and day.

Walter Rauschenbusch

Why do I tell you their stories? Because this is Christ the King Sunday. Next Sunday we begin a new church year. Today is the end, the culmination, the ultimate Sunday before little Jesus Baby New Year shows up with his sash next week and we enter Advent to do it all again. It is not incidental that we end the church year with Christ the King Sunday. The last word is almost always the most important word, and for Christians the last word is that Christ is king. If we pause and listen to those words, they will ring strangely in our American ears. Like bazillions of Americans, Jill is watching the Netflix series The Crown, and her fascination with the life of Queen Elizabeth stems from the fact that the notion of royalty is so entirely foreign to our American sensibilities. We don’t have kings. (That’s sort of the entire American point, isn’t it?) Except here we are, those of us who claim to be Christian in addition to—or before—we are American. And today we say that Christ is King. So what do we mean by that?

The options are those of the contemporary Christian titans, Billy Sunday and Walter Rauschenbusch. Though they lived a century ago, their distinctive approaches still drive our thinking today. Both bent the knee to Jesus as king, but their understandings of what that entailed were very different.

In one sermon (available on YouTube), Billy Sunday says he won’t rest until “this old world is bound to the cross of Jesus Christ by the golden chains of love.” But it is clear that for Billy Jesus’ reign is interior to the human heart. Throughout his career, he was criticized (as Billy Graham would sometimes later be criticized) for having as his close friends men like John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and while encouraging such industrial barons to place their souls under the reign of Christ, that encouragement did not translate into changing the way they did business or laboring to better the lives of suffering people. Billy Sunday’s message is an entirely personal, not public, one. He spoke to the individual heart in hopes that it would become the subject of Jesus the king. If Billy Sunday hoped for societal change at all, he assumed that the subjugation of the heart would somehow mysteriously, eventually, organically lead to social change. Overt Christian social action was absent from his religious understanding.

Walter Rauschenbusch, by contrast, was the original social justice warrior. For Walter, Christ’s kingship was not primarily of the heart, but of the outward world. In his last great work, A Theology for the Social Gospel, Walter Rauschenbusch states the hope that, with Christ as king and through the concrete social actions of his subjects, the very kingdom of God would emerge in our world. Injustice, suffering, and want would be overcome, and that requires that the subjects of Jesus first and foremost speak and act in the world boldly for social change. But Walter Rauschenbusch was criticized, too, and in his case there were some who thought he co-opted the Gospel to undergird a Progressive political agenda.

Christ’s kingship as a matter of ruling the heart or as a charge to social change…but might this be a false choice? The epistle lesson for today, which is the great Christ hymn from Paul’s Letter to the Colossians, tells us that Christ “has rescued us from the power of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son.” It then goes on to tell us what that means: “In [Christ] all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him…so that he might come to have first place in everything.”

The great biblical scholar and Anglican bishop N.T. Wright warns against what I’m calling the Billy Sunday-Walter Rauschenbusch dichotomy. One the Billy Sunday side, Wright says, “[Christians cry], we want a religious leader, not a king! We want someone to save our souls, not rule our world!” But of the Rauschenbusch perspective, Wright equally warns, “If we want a king, someone to take charge of our world, what we [really mean is that] what we want is someone to implement the policies we already embrace.”[i]

In Colossians, Saint Paul is clear and unequivocal that both perspectives are partial and incomplete, if not downright wrong. Jesus’ kingship is not only about social action. It is about “things visible and invisible,” and that most certainly includes the disposition of the heart. Being subjects of Christ the king means nothing less than crucifying our own desires, loves, and pursuits in favor of Christ’s own. It absolutely includes those moments in which we are driven to our knees as before a lord and king, to say “Not my will, but yours live in me.”

Jesus’ kingship is certainly a matter of the converted heart, but it is not only so. Paul says that “thrones, dominions, rulers and powers” are within the bounds of Christ’s kingdom. In other words, if any lead in ways that are contrary to the love and grace of God, and of God’s care for all people, then as subjects of Jesus we are required to serve Christ as king over any earthly leader, and we are compelled to speak out and act in the world for Christ’s love, challenging power, challenging the structures of society, declaring that God’s kingdom supersedes all earthly ones.

In other words, Billy Sunday and Walter Rauschenbusch are two equally essential sides of the same coin. They are dopplegangers in addition to being exact contemporaries. We need them both, as faithful witnesses to Christ the king. When we turn our hearts to Jesus and allow his heart to become our own, and when we then live and act in the world in favor of signs that his reign is in-breaking, then Christ really does become king. And for his subjects, in him all things hold together.

______________________________________

[i] Wright, N.T. Simply Jesus: A New Vision of Who He Was, What He Did, and Why He Matters, pg. 5.