In the Gospel today, the resurrected Jesus appears to the disciples, but as with every other resurrection story in the gospels, the disciples have trouble recognizing him. When confronted with the risen Lord, there is startlement, confusion, doubt, testing. Mostly, there is the fatalistic inertia of what the disciples expect the world to present to them, and when the world before them breaks that mold, they don’t know how to respond or what to do.

How like them we are. We are raised and formed to expect the world to be a certain way. We believe in a regular, even pedantic world, in which all is mundane and/or explicable by processes that can be nailed down and defined. If anything ever surprises us, the surprise only lasts until we have had a chance to figure it out or explain it away. C.S. Lewis perhaps articulated our way of being in the world most aptly in his recasting of “Twinkle, twinkle, little star”: “Twinkle, twinkle, little star. I know quite well just what you are. You are just revolving gases, forming into solid masses.”[i] There is no wonder here.

When something happens to us that doesn’t fit the mold, when we have an encounter that truly and inherently slips our understanding and upends our expectations, we react with incredulity. The confusion is usually too much for us, so we willfully ignore the rub and go on with our lives as though it never happened, like those followers of Jesus mentioned in the Gospels who ultimately find the inexplicability of Jesus too much to take and go back to their old lives.

As we learn in today’s Gospel, Jesus will not have it so. Resurrection has happened. It will not be explained rationally or by the mundane, and its inexplicable reality confronts the Twelve. And Jesus will not allow them to lapse back into their old way of seeing the world. Jesus is insistent, displaying an urgency to the disciples rare in the Gospels. That the disciples reckon with Easter, that they lean into it rather than furtively flee, is clearly of vital importance to him. Why? What difference does it make?

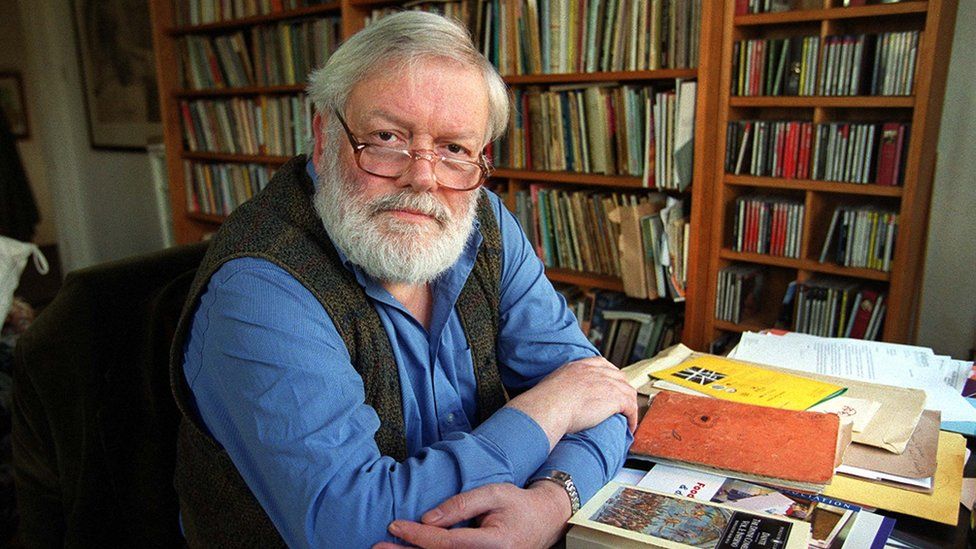

On Palm Sunday morning, as I was driving to the Cathedral, on NPR Krista Tippet replayed her 2016 interview with Irish poet Michael Longley.[ii] Longley is known, along with Seamus Heaney, as a poet of “the Troubles,” the decades-long socio-religious conflict in Northern Ireland marked by terror and civilian casualty. Even before the Troubles, Longley’s earliest formative memories are of his father, a trench warfare soldier in World War I, screaming through his nightmares in the middle of the night. All that is to say, the subject matter of much of Longley’s poetry, like his life, is grim. And yet, somehow through the grief and vexation of his verse, there is a luminescence to Longley’s poetry. Somehow, he recognizes that there is, always, a dual reality at play in his encounters with the world: the mundane and something else.

One of Longley’s most well-known poems is “the Ice-Cream Man,” about a local man who owned an ice cream shop and was murdered by a sectarian. The man’s shop, loved by all, had featured twenty-one flavors of ice cream. After the murder, Longley’s young daughter took a basket of wildflowers and laid them on the sidewalk outside the ice cream parlor. What was to most passers-by unnoticeable, was to Longley a revelation. In his poem, he begins by listing flavors of ice cream—Rum and raisin, vanilla, butterscotch, walnut, peach—but then transitions to a seemingly endless list of wildflowers: “thyme, valerian, loosestrife, Meadowsweet, tway blade, crowfoot, ling, angelica… marjoram, cow parsley, sundew, vetch…” The effect is that Longley finds a path from something ugly to something beautiful, or perhaps better said reveals the beautiful in the tragic, without for a moment letting go of grief. He sees a dimension of grace where others see only the brute and prosaic layer of reality.

Various sources claim that Michael Longley is an atheist, and he calls himself a “sentimental disbeliever.” But when pressed, Longley offers more nuance. He says, “I do believe in the transcendental. I believe that poetry and art, without a transcendental element, doesn’t really exist for me…. [It] is all a transcendental experience for me. My heart stops when I discover an orchid…And then, when I hear a bird sing, it goes through me like an electric shock. These are the things that matter to me. And I would call that transcendental.” Though a poet, one gets the sense that he means this literally and not only as metaphor.

And, despite his protestation that something more religiously organized is not for him, Longley also slips in the admission, “Once every four or five years, I take communion, and I believe in the poetry of it — the poetry of it.”

What makes the difference? How is it that the world is neither fatalistic nor merely inert stuff to Michael Longley? How is it that a life lived in the very shadow of such pain, and grief, and terror finds itself repeatedly taken aback by beauty and wonder? Longley explains it as the poetic sensibility. He tells Krista Tippet, “I have this secret life no one knows about…For me, it’s quite an extraordinary gift to see something beautiful…[It’s] extraordinary. And it’s a way of having more than one life.”

Intriguingly, Longley also borrows a phrase from Horace, and says he, and poets like him, are, in fact, “priests.” The basic meaning of “priest” is, of course, to be a conduit of the divine, to communicate truth that otherwise risks being undetected, and where most see only death, Longley sees the buds of new life. Where most see only grief and pain, he encounters nascent hope. Where most see shadow and drab gray, for Longley the world shines with color. Michael Longley sees a dimension of reality that most of us, most of the time, miss, and in response he cannot help but share that vision with the rest of us.

Longley lives, as he says, two lives at once. The first is the life that recognizes fully and well the world’s tragedy and, even more often, the world’s numbing banality. But the second life is the life that encounters, knows, and is a conduit of the beautiful, the poetic, and (dare we say it) the miraculous that exists side-by-side with—and in—the everyday. Longley calls this “adoration.” Speaking of his poetry, Krista Tippet calls it (despite Longley’s claim of disbelief) “religious in the best sense of the word.”

Michael Longley helps us understand Jesus’ insistence with the disciples today. I would call Longley’s way of being in the world an Easter sensibility. He has seen and recognized the miraculous in the mundane. His eyes are open, and no matter how unrelentingly the world grinds, he will not shut them. Jesus, as the Resurrected One, knows that this makes all the difference, for the disciples, for us, and for the fragile world in which we live. Because Easter people—people who look upon the world and see a different dimension of reality, who see wonder, beauty, and the presence of the living God—cannot help but live differently as people of hope, and love, and grace. That living, in turns, redeems the world, making Easter ever more a reality.

At our Sunday evening Celtic Eucharist, The Well, we often end our worship with a post-Communion prayer from the Church of Ireland that embodies for me this Easter sensibility. It asks that we remain awake, that we encounter the risen Christ, and that we live in response to that wonder. We pray this:

“Strengthen for your service, Lord, these hands that holy things have taken; may these ears with have heard your Word be deaf to all clamor and dispute; may these tongues which have sung your praise be free from deceit; may these eyes which have seen the tokens of your love shine with the light of hope; and may these bodies which have been fed with your body be refreshed with the fullness of your life; glory to you forever. Amen.”

[i] I first heard this from the Very Rev. Herbert O’Driscoll, who attributed it to C.S. Lewis. There are many versions of this ditty floating around the internet, attributed to various authors.

[ii] https://onbeing.org/programs/the-vitality-of-ordinary-things/