Month: November 2020

Advent and the Second Coming

Today we enter the season of Advent. It is, as churchgoers have heard preached innumerable times, a season for disrupting norms, stepping outside of our typical routine, taking a break from the usual crush of our lives, granting ourselves permission, patiently and without distraction, to prepare ourselves for the return of the Lord.

But seriously, can you imagine a year in which we need Advent less? For eight and a half months life has been one long season of Advent. Our norms have been so disrupted for so long that we have trouble remembering what they were. Many of us may even have settled into such a somnolent, hazy state-of-being over the months that we’ve almost forgotten the world ever was normal. That is, until something like the Thanksgiving holiday jars us into remembering, as we cancel plans to be with family and friends, set fewer places at the table, connect to give thanks over Zoom because it’s better than nothing. Then we awaken from our stupor like Rip Van Winkle, and we are reminded that we are waiting, and waiting, and waiting.

Of course, we are waiting on a vaccine against COVID-19, so that our lives can return to normal. Promising news has been released in the past couple of weeks about four separate vaccines that appear to provide solid protection against COVID.[1] Hopefully, these vaccines will be available by the spring. That said, no one is suggesting that our world is likely to be as carefree as it was before COVID’s emergence. Like medieval societies that learned to live with the plague, we will be negotiating coronavirus from now on.

Often, in this most surreal year, it seems as if we’re waiting on the other shoe to drop. Every time some new horror emerges—remember when “Murder Hornets” appeared in the Pacific Northwest a few months ago?—we catch ourselves saying with a nervous laugh, “Thanks, 2020.” Other events, including racial strife and a presidential election, are too grim even to muster an anxious chuckle.

We want these things, and everything related to 2020, to end. We want something new and hopeful to arrive. We are exhausted by our waiting—we’re at our wits’ end—and so rather than celebrate Advent, we may find ourselves saying, “Enough waiting already!” But what if we’ve misunderstood Advent all along? What if our conventional notion of waiting as the anticipation of a chronological end or beginning is different from what Advent is all about?

Today in Mark’s Gospel we read the last portion of what scholars call Mark’s “Little Apocalypse,” the final verses of a harrowing description of terrible things, both natural and manmade, that will happen in the world. For two thousand years many have contended that this passage refers to the end times, predicted when the events would occur, and attempted rationally to interpret events in their own lifetimes as evidence that the waiting is over and the end has finally arrived.

The problem with such scenarios is that, so far, each one has been wrong. And that’s because the events mentioned in Mark 13, though terrible, are terribly common. In other words, all the things described just before today’s reading—wars, rumors of wars, earthquakes, famines, betrayals, and the tearing down of the temples that define our lives—happen all the time. They happened yesterday. They’ll happen today. They will most assuredly happen tomorrow. Yes, they are terrible. And yet, the world keeps spinning.

Then, there is that curious promise by Jesus, that his own “generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place.” Was Jesus himself wrong? Did he misread God’s plan and intention? I don’t think so. I think Jesus understood entirely, though we do not. See, I don’t believe Jesus is talking about the once-and-for-all chronological end of the world or a future event upon which we must wait for Jesus’ return. That’s not the character of Advent waiting.

I believe Jesus means it when he says that the generation alive when he spoke would encounter both the terrible events he describes and his own return, just as I believe every generation since, including our own, has experienced these things.

In other words, what Jesus reveals today is what some theologians have called “sapiential” or “realized” eschatology. That means that, rather than the return of Jesus occurring at some future moment at the end of time, the return of Jesus happens now, in the midst of the trying and terrible things we encounter each day. If we keep awake, if we have quickened hearts and open eyes, then as our very lives skirt disaster, the Son of Man returns with power and glory, girding us and transforming us in the midst of the events around us.

Let me tell you a story. The summer my son Griffin was five years old, Jill and I spent a hot summer day with him at a beachfront water park. Because we were splashing in the water all day, as still relatively new parents it didn’t occur to us to monitor Griffin’s water intake. Upon leaving the park in the late afternoon, within minutes of strapping Griffin into his booster seat, he became wilted and lethargic. Foolishly, we let him sleep, and it wasn’t until a few hours later when we couldn’t rouse him that we realized something beyond fatigue was terribly wrong. And so, I strapped my limp son back into his booster seat and careened along the twenty miles of highway to the nearest emergency room. The waiting of that drive was an eternity, and for the first few minutes I tried—hyperrational creature that I am—to reason my way to a solution, to power my own way through the waiting to its end and the arrival of something different. I rehearsed the day and the wrong turns we’d made, as if I could undo them. I negotiated with the cosmos how this would never happen again. Very quickly, my thinking exhausted both my body and my hope, but it didn’t remedy the mess I was in or get me to the hospital any faster.

And then, at some point along that dark, frantic, and lonely drive, an old church camp song, Taize-like in its repetition, arose in my consciousness. My mind quit racing and I began singing it over and over:

Father, I adore you, and I lay my life before you. How I love you.

Jesus, I adore you, and I lay my life before you. How I love you.

Spirit, I adore you, and I lay my life before you. How I love you.

In the midst of the song, Christ returned, his presence as real to me as the air I breathed. Like the eye of a hurricane, Christ created a stable and peaceful center in the midst of the storm and met me there. I could not have found that place by myself. The best I could do was keep my eyes open, stay awake to the arrival of Jesus as the doctor and nurse worked faithfully to awaken my son.

The experience wasn’t rational. I didn’t think, “If I love God, everything will work out.” This was something different. Though the harrowing event of Griffin’s heat exhaustion was nowhere near over—and, indeed, there was no way to predict its outcome—in an essential way my waiting ended. Who I was in the midst of the ongoing turmoil was transformed by Christ’s return. The Season of Advent is about waiting upon the return of Jesus, but it need not look to the chronological future. Advent is about the return of Jesus in every generation, including our own. After eight and a half months, you may be exhausted in your body, and you may nearly have exhausted your hope. But it turns out that casting our gaze to 2021 or any future is myopic. Who knows what may or may not happen then? Rather, Advent is about staying awake now, in this and every moment, for the return of the Son of God who comes again and again and again, to end our waiting and transform our hope into the joy of Christ’s own living presence. When that happens, it turns out that the old world does, indeed, end, and the new world begins. And no terror, no turmoil, no illness, no threat can touch that world. Keep awake! Christ returns, perhaps this very day.

No gorillas in the carport

| During this Thanksgiving season, I am reminded that growing up in Arkansas, each Thanksgiving Day my rather large family would gather around my grandparents’ dinner table for a feast of turkey, dressing, dirty rice, and more varieties of pie than I could count. Before we could eat we were required to take turns around the table sharing what we were most thankful for. My grandparents, who vividly remembered the Depression, would offer thanks for health and prosperity. My parents would offer thanks for their children. Normally the children would give thanks for our friends or our favorite toys. But one year, when my younger brother was still small enough to be sitting on the phone book, he piped up and said, “I’m thankful that there’s not a gorilla in the carport.” We stared at him. My father considered chastising him for making a mockery of such a solemn family tradition. But then we all realized that it was a good thing that there wasn’t a gorilla in the carport. We were all thankful for that. And so, that, too, became part of the tradition. Now each year someone is sure to give thanks — and we’re working on a forty-year record, though our thanks will be expressed over Zoom this year — that there are still no gorillas in any of our collective carports. (You should know that when I moved to Houston I called the Zoo to make sure any and all primates are kept securely under lock-and-key.) At first glance, it may seem like a silly family tradition. But not so. Its import is that it reminds us each year of family members gone — all of my grandparents are now deceased — and of a formative time in our family’s life, when children were being raised, family security was being established, and love was abundant. It reminds us of where we have been, who we were becoming at that time, and who we still hope to be. That is, I believe, what all good traditions do. They remind us of where we’ve been, who we are becoming, and who we still hope to be. I pray that in your family, your walk with God at the Cathedral is a cherished part of your tradition. If not, then I invite you this season to nurture a new tradition: Make the Cathedral a central part of your life. Talk to God, listen for God, and commune with your brothers and sisters in Christ, in all the ways — virtually and in person — the Cathedral provides. Allow Christ Church to be the lens through which you remember where you’ve been in life, honor the disciple you are becoming, and look forward to the Christian you hope to be. And know that for you, I am thankful. |

E Pluribus Unum

Everyone is wondering whether this sermon will be about the elephant in the room. So, I might as well name it. We have experienced a hugely stressful election season. The campaign included moments that, just a few short years ago, we’d not be able to concoct or imagine. Finally, a candidate has prevailed, though he isn’t the candidate some would have chosen. He is flawed. His age makes us uncomfortable. He gets on the couch even though he knows he’s not allowed. He chases the cat incessantly. I am, of course, referring to the hard-fought mayoral race in the town of Rabbit Hash, Kentucky, which so mesmerized the nation these past weeks. Rabbit Hash election officials have, as of this morning, called the race, and the new mayor is a six-month old French bulldog named Wilbur. It turns out Rabbit Hash, Kentucky has a habit of electing dogs. Wilbur succeeds Mayor Brynn, a pit bull who served from 2016-2020. Describing Wilbur’s transition plans, campaign manager and dog owner Amy Noland says of the mayor-elect, “He’s done a lot of interviews locally, he’s had a lot of pets, a lot of belly scratches and a lot of ear rubs.”[i]

Humor is a blessed, momentary relief from the crush of emotions that have accompanied, and continue to accompany, not only this election but our national, civic life on the whole. The past five days have simply compressed all of those emotions into a much narrower wavelength, so that people across the political aisle have experienced the oscillation of joy and heartbreak, fear and relief, in such quick succession that we are exhausted. As I stand before you, I myself have gotten precious little restful sleep in the past week.

At a cocktail party just prior to the coronavirus pandemic, I heard someone ask with regard to our national circumstance, “Why can’t we just get along?” The speaker intentionally borrowed his words from Rodney King, and it is a tantalizing hope: Why can’t we, despite our deep differences and the vitriol that infects our shared life, just get along? But the question too often really means something like, “Why can’t the world just stay the way it is: comfortable for me? Why can’t others simply acquiesce to my preferred vision for our country? Then we would all get along.”

We recognize the inadequacy of the request when we take a moment to remember the heartrending circumstances in which Rodney King first uttered those words. They weren’t, for him, superficial. He had been beaten by police officers and in the weeks thereafter, as he was pushed and pulled and manhandled anew in the media, his cry was as the Psalmist’s, “How long, Lord? How long?”[ii]

We can’t just all get along, not in the superficial sense, because there are competing visions for the United States that undergird our disagreements. Those visions are important. When he spoke here a couple of years ago, Episcopalian and author John Meacham said it is as if various people and parties are competing for the soul of America. When the stakes are that high, pretending that they don’t exist or don’t matter is not an option. So, what are we to do?

Our church—the Episcopal Church—actually grants us resources that many other traditions lack. Henry VIII’s desire for an annulment from Catherine of Aragon and the subsequent sequence of events involving both church and state in sixteenth century England led to civic rancor, factions, broken relationships, and many gruesome deaths. Tudor England bears more than a few rough analogies to our own time. In the late 1550s, after the English people had exhausted themselves with mutual recrimination and disdain, the newly-ascended Queen Elizabeth, through force of her healing character, said “Enough!” She established a new norm that provided for a wide latitude of belief and practice, both religious and civic, and declared that, going forward, the English people would, no matter what, stand together as one nation. From then on in English religious and national life, schism—walking away, walking apart—became a greater and graver sin than heresy. In other words, the English people would commit to work together, in shared identity, through any challenge. Their disagreements would be real and hard-fought, but they would not break communion with one another. The English only forgot this once after that, and the English Civil War a century later quickly reminded them of Elizabeth’s wisdom. And this served England exceptionally well in the intervening half-millennia. I dare say, without Elizabeth in 1559, a unified England could not have withstood Hitler in 1940.

In our own context, the motto of the United States is E Pluribus Unum, “From many, we are One.” The motto appears on our currency, our passports, and the official seals of all three branches of our federal government. In the past few weeks, Presiding Bishop Michael Curry has honed in on this. Bishop Curry traces the origin of E Pluribus Unum to the great Roman orator and statesman Cicero. In the year 44 B.C., Cicero wrote a letter to his son outlining the obligations of one who loves his country. Cicero said, “Unus fiat ex pluribus,” which translates, “When each person loves the other as much as himself, it makes one out of many.”[iii]

Imagine that. Our national motto isn’t about rugged individualism. It isn’t about wishing everyone else would get on board with my vision for the country. It is ultimately about love. E Pluribus Unum. “When each person loves the other as much as himself, it makes one out of many.”

How do we do that? We don’t give up our convictions, or our unflagging efforts to mold our nation into a “more perfect union.”[iv] But we do remember that we are bound together in love with every one of our fellow Americans. Every one. Even with those with whom we disagree. Even those whose opinions we believe are deeply misguided.

Our culture, including and especially social media, encourages us to react to one another with knee-jerk shibboleths in response to someone else’s opinion: “Socialism!” “Fascism!” “You want to take my healthcare!” “You want to take my guns!” But what humility might each one of us discover if we push back against our visceral reactions and put on lenses that seek to see the other in the most positive light? What avenues for understanding might appear if we resist imputing the worst motives to our neighbors? How might our conversations track differently if we begin by granting that the person with whom we speak hopes for a United States that strives for the well-being of all?

I am not naïve. Not everyone has virtuous motives, not everyone around the water cooler and not everyone in the halls of power. But I believe that most—the overwhelming majority—do, including those whose political opinions baffle and discomfit me. And if they do—if they, like me, want for love of all to render One out of Many—then there is still gracious and ample room to speak together, walk together, and work together toward making the United States a light to other nations.

We will have a new president in January and likely a new chapter of shared government between the parties. This grants us new opportunity, if we will be open to it. Each American, from wherever one stands across the political spectrum, can and should argue vociferously over competing visions, laboring tirelessly for justice and a truer approximation of God’s kingdom on earth. If, in the process, we commit to walking and working together, then the outcome won’t be entirely one vision or the other but something in between. (There used to be a name for that in American politics…) And yet, the fact that we have made the effort committed to one another is itself an in-breaking of God’s kingdom. We must never forget that.

We, here, are Anglicans, and as such our religious life has for five hundred years been bound up with civic life. And so, perhaps we have eyes to see the way in which Cicero’s words precedingly echo Jesus’ own. “When each person loves the other as much as himself, it makes One out of Many.” At the end of the day, then, E Pluribus Unum is its own call to follow in our civic life as in the life of Joshua and the Israelites today, the lure of God’s love instead of any national idol placed before us. Joshua says to the people today, “Now if you are unwilling to serve the Lord, choose this day whom you will serve… but as for me and my household, we will serve the Lord.”

Beyond any political election, that is the real choice always before us. In our visions for America, but also in the ways we interact one with another and define or seek to understand those with whom we disagree, do we serve the Lord of love? In this household of faith, the answer is clear. And that gives me hope on this day of Resurrection. Amen.

[i] https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/ncna1246569

[ii] Psalm 13

[iii] https://bringinganahome.wordpress.com/2017/08/13/e-pluribus-unum/

[iv] Preamble to the United States Constitution

Always neighbors; never enemies

Our church—the Episcopal Church, which is the American expression of the Anglicanism forged in the Church of England—has always been engaged with the workings of the commonweal. After all, Henry the VIII rendered the Church a branch of the government, which caused more than a few problems for the church, to be sure, but also allowed the church to remain attuned to the needs, the concerns, and, indeed, the dangers that faced the nation and its people.

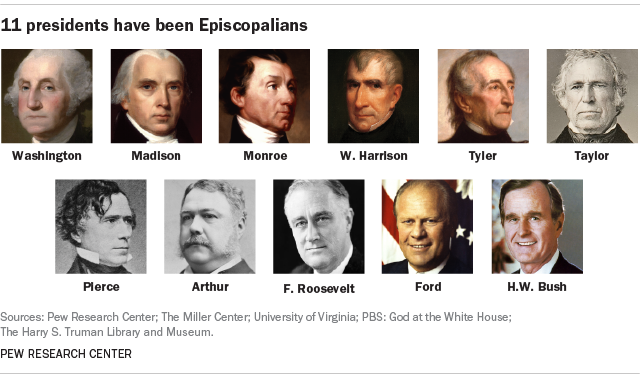

In the United States, that tradition of engagement by Episcopalians with the civic life of the nation has remained strong. There have been more Episcopalian presidents than from any other denomination, as one singular example. From the halls of power to the power of the voting booth, Episcopalians listen, pay attention, form opinions, hold convictions, and then—most of all—act.

All of that is good, and especially so when we arrive at a day like today and a national election. Our nation desperately needs Episcopalians to participate in the commonweal in ways that usher in the kingdom of God. That’s not theocracy in the making. Rather, it leavens the world with grace.

But somewhere along the way, Americans have come to mistake fellow Americans with whom they disagree as enemies. We impute to them the worst motives and turn their views into caricatures, and we harden our own views until they lack all nuance and fall prey to the sin of self-righteous certainty. And the result is the opposite of the Gospel of Jesus. Instead of fostering reconciliation, we fracture relationship.

My good friend, the Rev. Daryl Hay, said this past Sunday, “Christians don’t have enemies, only neighbors.” Anyone who reads the Gospel with care knows Daryl is correct. So, on this election day, on which so much of such import is admittedly at stake, how are Christians, and particularly Episcopalians, to respond? I hope we will vote, and I hope our votes will be cast through the lens of the Gospel. Beyond that, however, I hope we will model for the rest of the world what it means to love our neighbors.

The Very Rev. Anne Maxwell, Dean of St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Jackson, Mississippi, shared with me a pledge that the members of at least one parish have committed to take this election season. It is steeped in the Gospel. I will take this pledge, and I encourage you to consider taking it too:

A Pledge for the Presidential Election

As a person of faith committed to the life and teachings of Jesus, I make this pledge to all people

regardless of their political beliefs, whether we are in agreement or disagreement, and regardless

of who wins the election.

With respect to my words and actions, whether in person or through social media, I pledge and

commit myself, both before and after the election –

To love others as Jesus has loved me (John 13:34);

To treat others as I would want them to treat me (Luke 6:31);

To love my enemies, do good to those who hate me, bless those who curse me, and pray

for those who abuse me (Luke 6:27-28);

To “proclaim by word and example the Good News of God in Christ” (Book of Common

Prayer, 305); and

To “strive for justice and peace among all people, and to respect the dignity of every

human being” (Book of Common Prayer, 305).

This I pledge in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.