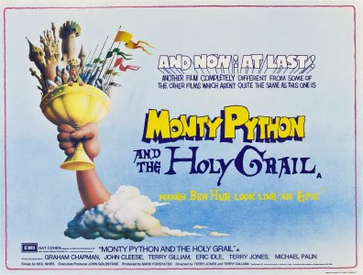

From about the age of ten until I was old enough to drive, my New Year’s Eve tradition, with either my brothers or friends, was to stay up late and watch Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Yes, I can recite the lines with you, whether it be the Knights Who Say “Ni”, the Black Knight, brave Sir Robin, or Tim the Enchanter, who warns of the killer rabbit with “nasty, big, pointy teeth.” But my favorite scene is when the cohort of monks processes through a squalid medieval village, chanting, “Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem,” which translates, “Pious Lord Jesus, grant them rest.” The Python troop’s spin on the Dies Irae is, of course, to have the monks, with each line, whack themselves in the forehead with a board.

Monty Python captures in two minutes of film what is perhaps the prevailing view of Christianity from the actual Middle Ages until today. Whatever else our religion is, our subconscious assumptions about it include a heavy weight, self-flagellation, and an undercurrent of foreboding or even doom. Sooner or later, Christianity seems to be about whacking ourselves about the head with a board.

We can surely understand why this is so, and the rationale comes from the red-letter words of Jesus himself. This very day, immediately after Peter has acknowledged that Jesus is “the Christ, the Son of the Living God,” Jesus explains to the disciples that he, “must undergo great suffering, and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed.” And then Jesus counsels those who would follow him that they must, “deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.”

That appears to seal it. Christianity involves sacrifice, and pain, and suffering. While taking up the cross may be, for us, a metaphor, its associations are unavoidably ugly. That’s why, I think, so often behind the smile of the most ardent Christian one finds a note of apprehension and unease. We worry that if we aren’t carrying the cross we are being unfaithful, but if we do carry the cross our lives will be consigned to difficulty and pain. Sooner or later, we sense that it’s all about whacking ourselves in the head with a board. What are we to do?

First let me say that such an interpretation of Christianity, whether overt or subliminal, has been the root of much pervasive abuse over millennia. For example, until very recently in many churches (and still today in some), when a physically or psychologically abused spouse would confide in her priest or pastor, she was liable to receive the response that, as a faithful and submissive wife, her husband’s anger was her cross to bear. People of color were taught that their social location was their immutable cross to bear and that faith required them to bear it without complaint. LGBTQ Christians similarly have been told that repressing their sexuality is akin to taking up their cross. Innumerable others shouldering grief, or pain, or disappointment–including illness or loss of loved ones to untimely death–have been told that their suffering is from God, to be borne as a cross and that the heavier the cross the greater their faith.

With every iota of authority that I can muster as a priest of the Church, hear me say that these interpretations are wrong. The Church has done egregious and long-lasting harm in perpetuating them. It is bad theology that says God will ask us to suffer for suffering’s sake. It is bad theology that says we must passively endure terrible things as part of our walk with Christ. It is bad theology that secretly thinks God wants us to bash our heads with boards.

How else, then, might we conceive of bearing the cross? How might we redeem this commandment from Jesus that we claim is the source of all redemption?

For that, we travel back in time millennia before Jesus, to the covenant God made with Abram. In Genesis 17 today, God renews that covenant. The covenant was first made five chapters earlier, in Genesis 12, and there in the covenant—the original promise from God—God explains why Abram is worthy of entering into this special relationship with God at all. “I will bless you,” God says to Abram, “so that you will be a blessing.”

When God reaffirms this covenant five chapters later, in Genesis 17, God renames Abram, “Abraham.” And Abraham is not the only one who receives a new name from God. His wife, Sarai, is also renamed “Sarah.” The change in her name is subtle but equally important. It is a grammatical change only, altering the form of her name from what had been the possessive. In other words, her old name had implied inward focus and concern only with what was hers. Her new name—Sarah—looks outward, toward and into the world that she and Abraham are called to bless.[i]

Make no mistake: In these two chapters—Genesis 12 and 17—God is saying to Abraham and Sarah the same thing Jesus says to the disciples. In the Gospel, Jesus says, “Take up your cross and follow me.” In Genesis, God says, “I bless you so that you will be a blessing.” They are the same thing, and yet the language in Genesis sheds entirely different light on the command in Mark.

Whatever it may mean to bear the cross of Christ as faithful disciples, it must always be a means by which the world is blessed. If there is a litmus test by which we can judge whether the burden laid upon us is part of our walk of faith, or whether it is laid upon us by God, then that is it, and it is worth saying again: Whatever it may mean to bear the cross of Christ as faithful disciples, it must always be a means by which the world is blessed. Bearing the cross of Christ may include suffering at times—indeed, it will—but only if that suffering is a blessing to someone. Bearing the cross may bring challenge; it may lead to difficult decisions; it may sometimes disrupt relationships; and it will definitely require us to confront powerful forces that can do us harm; but it will only ask such things of us if doing so facilitates God’s blessing upon the world.

Jesus indicts Peter today because Peter here (and not for the first time) has no interest in being a blessing. He will later learn and change, and he will become a blessing to many (including in his own suffering), but at this point in the narrative, Peter is completely self-absorbed by what being a follower of Jesus can do for Peter. And Jesus knows that faith, and our walk of faith, whether in time of ease or difficulty, whether in comfort or suffering, always begins with the question, “How can I be a blessing today? How can I bless those I love? How can I bless the stranger? How can I bless God’s good earth?”

The miraculous thing is, when we understand bearing the cross in this way, rather than as some foreboding and myopic walk of doom, we begin to experience intuitively what faith really is. When we bless, we become agents of grace and of God’s own gracious will. That Christian smile ceases to crack like a thin veneer and instead becomes an authentic expression of who we are and who we strive to be in the world. In other words, somewhere in the midst of our cross-bearing—somewhere in the mix of faithfully following God and pursuing grace—we find joy. Joy can reside alongside challenge, or sorrow, or pain, and joy’s presence redeems all these others. Joy renders them ultimately transient, whereas joy is permanent. This is what it means to lose one’s life for the sake of the Gospel and thereby regain it.

As we walk through this Lenten season, I pray we will be willing to bear the cross of Christ, in the deep knowledge that what is asked of us is that we be a blessing in our doings large and small, so that in us all the world will be blessed.

[i] https://weekly.israelbiblecenter.com/the-meaning-of-the-hebrew-names/